The most honest art gallery in the world.

Highlights

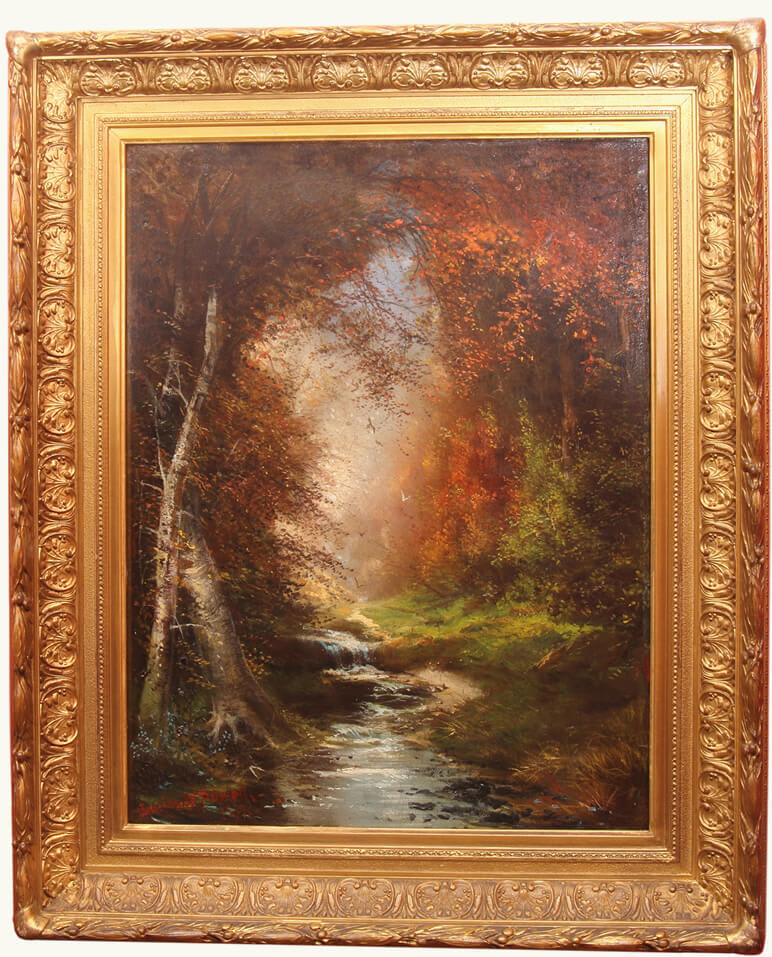

LONG ON COLOR

In 1871, Samuel P. Long penned "Essay VII, Color" in his book Art: Its Laws and the Reason for Them, Collected, Considered, and Arranged for General and Educational Purposes. Granted, it is a very long title, but an important book on art for the general public that time. Interestingly, Mr. Long, who was a Counsellor at Law in the United States, had been a student of Gilbert Stuart Newton at the British Royal Academy in the early 1800s. Stuart’s mother, in turn, was the daughter of American portrait artist, Gilbert Stuart. Our distinguished Counsellor, himself, was a landscape painter and exhibited at The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the Boston Athenaeum. During this time and into the last quarter of the 19th century, the academies taught only representational art, no Impressionism (although it is representational) or Abstract art (nonrepresentational). An artist’s hope of success lay almost entirely on acceptance at the salons. Strictly regimented, with a lengthy course of study combined with rules on linear perspective, the handling of light, colors to be employed, the subject matter, and how the paint was to be applied and with what brushes, strict academic training fell out of favor by the end of the 19th century. This manner of painting was considered to be not only a creative endeavor, but an intellectual one, in sharp contrast to the emotionalism of much of the 20th century "modern art", the primary basis of which is deconstruction of form and the use of unrealistic distorted compositions and colors. Long wrote his book near the tail end of the long reign of the academies and his essays insight to the thinking of 19th century artists in flux.

Long refers to the "mysteries" of color and the mysterious effects of light and dark (chiaroscuro) in a painting. Chiaroscuro creates space and body and the proper application of light and dark in a painting allows subject to be detached from the background to advance and recede—in other words it provides dimension. Regarding color, Long states that "although most enchanting, it is for the general purposes of imitation, the least essential of the component parts of painting". In his mind, the most important foundation elements of a fine studio painting were invention, composition, design/drawing, chiaroscuro and lastly, color. Invention was that process by which the artist composed a "story" or theme from his mind, not from an actual scene or subject. The source could be from poetry, history, mythology, religion or simply the mental invention of the artist. Composition is another "mental operation" that consisted of the artist making "picturesque arrangements to please the eye" and most importantly "preserving a correspondence between the material employed and the sentiment of the subject". To preserve or capture the sentiment of the subject one would think that color would be very important; however, Long forges ahead with what he considers the foundation of a painting—the drawing, stating that "color apart from outline is only an unmeaning glare". The technique of chiaroscuro was used to "render the surface of a picture "agreeable" to the eye by dividing it into masses of light and dark and "to assist sentiment and give expression". The lights and darks of a painting, in his words, "should be so arranged as to assist sentiment and be an echo to the sense". Tenebrism, a related painting technique, which Long may have lumped in with chiaroscuro, is a more dramatic version using a stream of light to cut through the darkness and emphasize the subject.

Color, is important in both chiaroscuro and tenebrism because of the application of high- and low-key colors used to create the effects. Long did recognize this and the other attributes of color in his Essay VII. He states that color gives reality to a subject and that the "beauty of the atmosphere, the morning dawn, evening splendor; the tender freshness of spring, the fervid vivacity of summer and the mellow abundance of autumn" is almost entirely dependent on color. He recognized that color heightens joy, inflames anger, and deepens sadness--important expressive concepts to modern nonrepresentational artists. Color was important to the early- to mid-nineteenth century artists in a different way than to the late 19th century and early 20th century artists. As artists began breaking rules of academic art to explore new dimensions in painting techniques, visualization, and color theory, the expression/emotion of the artist and the process and action of applying paint became more important than the realistic portrayal of subjects in their proper form, perspective and color. Just as now, color to Long and other artists of his time, was "used to characterize the various qualities, textures, and surfaces of bodies in all their various situations of light, shadow and reflection". To varying degrees, shadow and reflection have been significantly reduced in importance in nonrepresentational art where the perspective of depth is often absent, and color is used more for texture and visual impact.

Long was not an advocate of the academic "high finish" of the generation of painters that preceded him. Too much blending of the colors, a hallmark of this manner of painting, resulted in a highly polished finish that was passé at the time Long wrote his essays. He was an advocate of impasto (thick paint application with visible strokes) because it provided "brilliancy" and also texture, which were very important to the Impressionists and later artists, but also to some of the earlier Renaissance painters. He made the association between color and detail, essentially saying to apply only the colors necessary to provide the overall appearance and avoid the minutia of exacting detail; it is the eye that processes juxtaposed colors that "echo the sense" of the subject. We cannot say whether Long approved of the Impressionist style of painting; however, I think expressionism might have offended his "senses". It would be quite instructive to us if we could examine paintings by Long in order to assess his command of the "mysteries of color."

We will undoubtedly visit again to see the art in this remarkable gallery. We brought home a watercolor and have the confidence we were dealt with openly and fairly.

William and Susan L.Jerry & Joan - Thanks for your hospitality and helping us find this beautiful new piece for our home. Until next time...

Adrienne & Jon W.Thank you again so much for the information, Jerry.

Allison G.This sounds perfect. I am really happy that after being in the family for a hundred years, they will be in good hands at your gallery. I was very impressed by your website and your dedication to and appreciation for fine art.

Antonia S.Such a lovely experience with Knowledgeable people passionate about art.

Beth Anne J.Thank you for including me on your mailing list. Every time I see Bedford Fine Art Gallery in my mail I know I am in for a treat.

Beth L.Let’s face it, paintings are expensive, and it can be a traumatic experience buying them. Jerry and Joan do as much as any vendor possibly could do to make the experience relaxed, warm, and joyful. We came away with a high level of trust and satisfaction, knowing that we got a square deal on some wonderful paintings and knowing that Jerry and Joan provide great customer support.

Beth and SamCouldn’t have been a better or easier transaction! Again, many thanks.

Betty D.When I first saw the painting, it reminded me of a time gone by, when life was so much more simple, where everyone was less in a rush, a time when everyone knew everyone, a time where people actually cared for their fellow man.

Bill B.It is a joy to have in our collection, and we will take good care of it, for the rest of our lives.

Bob L.We were so happy with Joan and Jerry’s customer service and expertise. I would recommend Bedford Fine Art Gallery to anyone that is looking for the special piece of art. You will be happy you reached out to them.

Bob and Christine M.Discovering Bedford Fine Art Gallery and working with Jerry and Joan to purchase our first picture from them has been a smooth and joyful experience — and we haven’t even met in person yet.

Bob and Theresa L.I drove 12 hours to meet the nicest couple and outstanding artwork that was perfectly and honestly represented. More than pleased with expertise, professionalism, and kindness genuinely exhibited by Jerry and Joan.

Brent & Sarah S.Thanks for making my purchase so easy.

Brian C.It was truly a pleasure dealing with you and the Bedford Fine Art Gallery.

Brian C.Greetings! Thank you for your periodic emails. They are always welcomed.

CNLove your posts…thanks!

CarrollA truly incredible website. Really! I was "detained" there for almost two hours and have returned periodically. Pictures are worth thousands of words, literally. Any reader who heeds our advice and visits the site will be happy to confirm our praise. We encourage all to visit and get to know Joan and Jerry. Most knowledgeable, friendly, accommodating, and a pleasure to deal with.

Carroll and Carolyn K.Joan and Jerry Hawk’s Bedford Fine Art Gallery, located in the historic Bedford Mansion, near the Bedford Courthouse, offers an extensive collection of original 19th century paintings in their beautifully restored gallery...which continually attracts this appreciative collector and former museum trustee.

Charles F.I would highly recommend this Gallery for art.

Christopher C.In this age of internet shopping, few can pull off personalized and professional customer service, but Bedford Fine Art Gallery has perfected it!

Christopher K.Furthermore after discussing its acquisition with Joan not only did I find the entire process most pleasant but Joan agreed to deliver the painting the very next day which was in fact my birthday. I find this sort of old-fashioned business courtesy so rare these days. What a pleasure to do business with people like this! I wholeheartedly recommend art purchases from this company! They are simply the best!

D. H.Jerry - The painting just came alive. Please know how grateful I am.

D.G.S.Jerry, - Thank you and Joan for our visit Friday. You two make me smile.

D.S.Magnificent. Your love for your art collection is displayed in your gallery.

Dave N.I was very pleased with the way the communication between Gerald Hawk and myself was handled. Very prompt and efficient. I would recommend the Bedford Fine Art Gallery to anyone interested in their beautiful artwork.

Debra B.I am enjoying my artists work and their position in my Mechanicsburg home, as well as Williamsburg.

Doris B.Jerry & Joan offered the work fully restored and framed so it was ready to hang. They were easy to deal with which went a long way since I was buying from outside the US.

Ed H.A visit to the Bedford Fine Arts Gallery is a rare opportunity to see American nineteenth landscape, portrait, and still life paintings in a house-turned-gallery of the same era, in a region close to where some of the artists, such as The Scalp Level School, painted.

Ellen C.We have counted on the Hawks over the years to regularly discover incredible items whose quality and condition have ameliorated the artistic environment of our homes.

Frank B.Thanks again for the opportunity to own the work of an artist who is very important to us. We are extremely happy with this experience. Take care.

Franklin J.My introduction to Gerald Hawk came through an initial phone call. Not only was he knowledgeable of fine art and well connected with the collecting community, he was passionate for his love of art. He treated me with the greatest respect, honesty, and kindness. That was the start of a business relationship that has probably been the most enjoyable I have had the pleasure to experience in my life.

Fred C.Just to let you know the painting arrived in perfect condition and we are thrilled.

G. & T.Beautifully done - one can tell it is a work of love! The collection was impressive and the viewing of it , a pleasure. Thank you!

Gabrielle G.Proprietors Joan and Jerry Hawk have established a first class art gallery offering the very best in fine art, professionally arranged displays, state-of-the-art technology, and superior customer service.

Gary G.Thanks for the quick reply etc. Not what usually comes from those Big Auction House Players .. and NYC galleries. So it’s refreshing to experience the response.

Geoffrey H.I recommend BFAG to both the serious art collector and to the one who desires to cultivate a love for fine art. The Hawks are knowledgeable and accommodating, and their love for fine art goes far beyond making a sale.

Gus S.Absolutely stunning art!

Irene and Peter E.Very pleased. Don't hesitate to contact me when you get something in that you think fits my collection.

J.M.The more I look at Rose Point the more I like it.

James M.The new paintings are hung and look great, thanks for delivering.

Janet S.I am so happy with my completed “gallery wall” and wanted to thank you for all your help in putting it together.

Janet and George S.Jerry and Joan are simply amazing. Their knowledge and passion are second to none. Not only is the collection at Bedford Fine Art Gallery of museum quality, but their passion really inspires you, comforts you, and welcomes you in as a member of what seems like an exclusive club. We are blessed to know them.

Jason and Alyson L.The Bedford Fine Art Gallery was recommended to us by our neighbors. They were very impressed both by the wonderful artwork presented and the very amiable owners. So, one rainy day, we stopped in to see for ourselves. We are so glad we did! It was immediately evident that, for Jerry and Joan, the gallery was not a business but a passion.

Jeff and Cathy D.It’s not every day you meet people so kind, professional and passionate about what they do. Every detail was taken care of from the excellent online listing to perfectly handled packing and shipping once we completed the purchase.

Jeff and Lisa G.From the front door, you can tell you are going to have a very interesting, pleasant and peaceful experience. The art is wonderful. The owners have so much knowledge and the patience to share it.

Jeff and Sara K.My testimonial for my purchase of the C. H. Shearer painting is a five star one!

Jeffrey F.Our impulsive stop while strolling through town turned into a several-hour visit and, ultimately, resulted in the purchase of a unique painting that we could not resist. The Bedford Fine Art Gallery is a destination must that we highly recommend for anyone who appreciates classic American art and superior service.

Jennifer T.Thank you for your help finding 2 new beautiful paintings for our homes!

Jeremy & AdrienneWe really appreciate the time you took to research the history of the roses.

Jim C.Jerry and Joan are terrific to work with. They have a wonderful selection in their gallery, and they take time to learn your interests to aide in the selection of a great piece of art.

Jim K.It was a pleasure working with Jerry and Joan at Bedford Fine Art Gallery.

Jocelyn D.Awesome place. Thank you for your hospitality.

Joe and Zoey K.Jerry and Joan Hawk have an extensive knowledge of the artists, backgrounds, and artwork in their gallery that they love to share with guests . The time invested in the Bedford Fine Arts Gallery will be one of your most pleasant memories of the year.

John B.A gem in the middle of Pennsylvania.

John and Kathy D.Beautiful and wonderfully displayed paintings.

John and Paula L.Hi Jerry, the painting arrived today and I think it is a beautiful and I’m very appreciative and thankful to have it.

JonSince the first time I visited the Bedford Fine Art Gallery it has been a great experience. The owners are warm, humble, and true professionals with amazing expertise to guide new collectors in finding the right piece that speaks to them. The knowledge and passion they share is so refreshing and made the entire process, from browsing to the final decision, so exciting and a true pleasure

Josh B.Extremely knowledgeable staff and wide selection of high end paintings by listed artists.

Joshua J.It was such a pleasure to purchase artwork from Jerry. He is an honest man, who goes the extra mile (literally – he actually delivered a painting to me, over 6 hour drive one way!) to make sure the painting arrived safely.

Julie A.Jerry was of great help by purchasing a painting that had been in my family for over sixty years.

Kenneth L.Packed with fine art like visiting an art museum

KevinHello Jerry, I love it. Just what I had been wanting.

Kevin V.Very informative, welcoming, absolutely gorgeous art. Thank you so much for the experience!

Kit T.Hi Jerry and thanks for your quick response!!!!!

KkThank you very, very much for your response and expertise.

LVMany thanks to you for your care and context in telling me more about the artist and the market!

Laura W.We were especially appreciative of your patience with us and your knowledge of the art.

Lee S.Dear Jerry, Thank you for so generously taking your time to research my painting.

Linda R.I just wanted to check in to see how you are to tell you that I was reminded yesterday of what an awesome business you guys have going. I went to one of the other galleries that has some of my artwork, and the person that I was dealing with no longer works there. Everything was mass chaos, and they can’t find one of my paintings! Jeff and I already knew that we found a gem when we found your gallery but then we got to spend time with you in December and it was doubly confirmed! Thank you again for letting us be a part of your beautiful Gallery.

Lisa G.Jerry: Got the paintings—they look fabulous.

M.M.If I could give more than 5 starts to Bedford Fine Art Gallery, I would. Dealing with Jerry Hawk was timely, efficient and productive. His terms made it possible for me to buy it, and he collaborated with a local shipping outfit to pack and send the painting as well. (It was beautifully and securely packed.) I recommend Bedford Fine Art Gallery without reservation!

M.P.Jerry and Joan were honest and straightforward with me. Also, they made the sale easy and fair.

Margaret H.The entire transaction was very smooth and I had excellent communication the entire time.

Margaret R.On a recent trip to Bedford we visited the Fine Art Gallery and were impressed by the quality of the paintings displayed and by the discussions we had with Jerry. We purchased a painting and we expect to revisit the Gallery on our next trip to Bedford.

Marguerite and BobI am thrilled with my purchase and cannot thank the Hawk’s enough for their exceptional customer service, and knowledge of the artist's paintings they carry in their gallery.

Marian B.The owners, Joan and Jerry Hawk, were very knowledgeable about each work of art in the Gallery and the art market in general. We found them to be very honest and sincere and never pushy about making a sale despite our interest in several pieces. A few weeks later we decided to purchase an oil painting from them. The overall transaction and delivery exceeded our expectations and we love the painting. If you are interested in purchasing a fine work of art from a dealer you can trust, I would highly recommend Joan and Jerry of the Bedford Fine Art Gallery.

Mark B.What a great experience it was to make my first fine art purchase with you. Thank you!

Mark S.We have been very happy with the entire purchase process, from choosing a piece of art to the care Jerry and Joan gave the piece in order for it to look perfect in our home.

Mary and Monty B.Jerry and Joan have a beautiful collection to choose from and provided exceptional customer service.

Melissa and John P.Jerry and Joan have a beautiful collection to choose from and provided exceptional customer service.

Melissa and John P.Thank you for all your assistance with my recent purchase. Both you and your wife were very kind and knowledgeable.

Michael M.When I'm searching for an artist, or a tone and style that I love, I turn to Bedford Fine Art Gallery.

Michael M.I keep coming back to your gallery because I love your paintings.

Michael M.Jerry and Joan Hawk have created a haven for art lovers!

Michal J.We consigned 3 oil paintings with Jerry and Joan Hawk at Bedford Fine Art Gallery.

Mike F.Jerry and Joan made it a smooth and wonderful experience by putting us at ease with their knowledge and gracious manner.

Mike and Karen S.It was such a pleasure to buy our first piece of fine art from you both.

Mike and Kelly C.Thank you for your business with the lovely paintings.

Moira O.We recently consigned several pieces of art to The Bedford Fine Art Gallery. It is hard to part with treasures, but Jerry and Joan were most accommodating in meeting us halfway in West Virginia. We appreciate their professionalism, received prompt payment for the sale of the first art piece and look forward to continued successful transactions.

Pam and Mike F.Jerry and Joan were a constant pleasure to work with. I had been considering purchasing a presidential portrait of theirs for some time, but they never tired of my questions or repeated requests to see the painting. I hope to acquire more 20th and 19th oil paintings in the future.

Patrick N.We are now excited owners of several beautiful paintings and look forward to seeing what new pieces are added to the gallery. Working with Jerry and Joan was a great experience.

Patty and Jim K.You are very honest and a man of your word. Thank you very much Jerry!

R.K.What a pleasant and surprisingly exciting experience, purchasing my painting from the Bedford Fine Art Gallery became.

R.T.From the first call through receipt of the expertly packaged artwork, the Bedford Fine Art Gallery excels!

Randy B.If you are able to visit the gallery I would suggest giving a few hours to enjoy the artwork. One more tip.... if your satisfied how the paintings look online, they are much better in person. I know I'll be back in Bedford soon to purchase another!

Randy Scott F.I would recommend this hidden gem!

Rhetta G.Jerry, thank you for overlooking my stubbornness and indecisiveness.

Rich C.They provided a simple and seamless transaction.

Richard and Cassie F.Ken came and delivered the art. Everything is beautiful.

Rick M.I would like to give a personal recommendation from my first-hand experience with the Bedford Fine Art Gallery during February and March of 2024.

Rob K.Jerry Hawk's passion and knowledge really shine in Bedford Fine Art Gallery's excellent collection of 19th century art. I heartily recommend Jerry and his gallery.

Rob S.We love the new paintings and are so glad to know you and your amazing gallery.

Robert L.The painting is exactly what I have been looking for.

Robert M.Truly, you are the "The Most Honest Art Gallery in the United States.

Robert M.It was a delight to have several hours with some very interesting and helpful people.

Roger and Joy G.Joan made us extremely welcome on that first visit and we were very taken with the work of two artists. We returned the next day and enjoyed a relaxed opportunity to study the pictures again before we committed to purchase. Both Joan and Jerry were very knowledgeable and helpful but also allowed us some privacy to discuss the pictures ourselves. Once we committed to purchase they went "the extra mile" to help overcome obvious hurdles of packing for international shipping and the customs arrangements.

Russell & Liz C.Joan and Jerry are extraordinary to work with for the purchase of our painting. They are extremely knowledgeable about the painting and have been helpful finding historical information about the Artist himself. Our beautiful painting hangs proudly where all can see and enjoy it.

Ryan M.If you are considering a wall art purchase to decorate your home, we would highly recommend contacting The Fine Art Gallery. We look forward to seeing what new pieces will be added in the newly expanded lower level of the gallery.

Ryan and TriciaThey were both very knowledgeable and truly care about each and every piece that they own. Ultimately, I was able to take home my very first John Joseph Enneking piece, Woodland Whitewater, and I could not be happier with both the piece and my entire experience at Bedford Fine Art gallery.

Sam H.This wonderful gallery is often noted to be on par with a 19th century art museum or salon and is not to be missed, including meeting its’ purveyors of art, Joan and Jerry Hawk. Their discerning eye, thorough research, and care in selecting and presenting the best representative art of the period is most impressive.

Sarah H.Upon meeting both Jerry and Joan I knew I made the right decision. They are very passionate about art work and quite knowledgeable on the life and history of the artist. It was a pleasure doing business with them and I would highly recommend the Bedford Fine Art Gallery if you are looking for fairness, honesty and a genuine comfort level in either selling or purchasing fine art.

Scott & BarbetteVisiting with no intention of buying, we were treated to in depth information on each artist and piece that caught our attention. We untimately purchased two pieces that touched us. Art speaks to everyone differently and it is nice to have gallery owners who appreciate that.

Sheila and FrankWe recently purchased a beautiful original oil painting from Bedford Fine Art Gallery. We live in Virginia, and because of Covid 19 and our age, we hesitated on traveling to PA to view this painting. Jerry and Joan were very accommodating. We highly recommend Bedford Fine Art Gallery, if you're in the market for some quality art work.

Sonny and Carolyn B.I bought three gorgeous paintings from this gallery and the owners are simply the best.

Stefanie L.What an incredible experience as I was on the search for a still life by BS Hays. Bedford Fine Art Gallery offers a beautiful, historical environment with a personalized service, guiding you through lovely art offerings.

Susan M.I am so happy to have worked with the Bedford Art Gallery; the people were pleasant and knowledgeable. Their collection is beautiful.

Suzanne F.I also wanted to thank you for your detailed response.

Suzanne S.We are enjoying the painting. Happy holidays to you.

TeddyThe breadth and depth of Jerry's knowledge of art is very impressive. What I especially appreciated was his down to earth manner and his willingness to know his customers.

Theodora BYou are wonderful Jerry! Thank you so much. I'm glad I connected with you. You certainly know your industry! I appreciate all of your help.

Tim B.Thank you- you are very kind.

Tim S.We found Bedford Fine Art Gallery about a year ago. Most impressive was the level of customer service they bring to the table. They went out of their way to be as helpful and accommodating as possible. We bought a wonderful painting we love.

Tim and Mary H.In sum, Bedford Fine Art Gallery is an exceptional art gallery which fosters meaningful relationships based on mutual respect, trust, and an appreciation for the field of art history. I highly recommend Bedford Fine Art Gallery and I look forward to forging a lasting relationship with Jerry and Joan for years to come.

Tyler M.Personalized, smart, customer service designed to assist you in choosing the finest 19th century paintings anywhere—whether you know your style & you’re adding to it, buying investment art, or like me—walking in and being starstruck by a piece that calls to me with no rhyme or reason but must come home with me.

Tyna L.Gerry was amazing to work with. Called him totally out of the blue, to sell a painting from my mom’s estate. Promptness is an understatement.

Uri S.Buying a favourite picture and talking with owners was a wonderful experience. Looking forward to seeing what they post for sale in the future.

V.B.Thank you so so much.

Valerie K.Combining knowledge and passion with their friendly home spun appreciation for their clients, the Hawks are the most delightful respite from the usual gallery sales approach.

Vivian and Bennett L.I really enjoyed the art, but the house, decore and overall experience was also very enjoyable

William K.Just arrived. Looks great. Thank you.

William M.We will undoubtedly visit again to see the art in this remarkable gallery. We brought home a watercolor and have the confidence we were dealt with openly and fairly.

William and Susan L.Jerry & Joan - Thanks for your hospitality and helping us find this beautiful new piece for our home. Until next time...

Adrienne & Jon W.Thank you again so much for the information, Jerry.

Allison G.This sounds perfect. I am really happy that after being in the family for a hundred years, they will be in good hands at your gallery. I was very impressed by your website and your dedication to and appreciation for fine art.

Antonia S.Such a lovely experience with Knowledgeable people passionate about art.

Beth Anne J.Thank you for including me on your mailing list. Every time I see Bedford Fine Art Gallery in my mail I know I am in for a treat.

Beth L.Let’s face it, paintings are expensive, and it can be a traumatic experience buying them. Jerry and Joan do as much as any vendor possibly could do to make the experience relaxed, warm, and joyful. We came away with a high level of trust and satisfaction, knowing that we got a square deal on some wonderful paintings and knowing that Jerry and Joan provide great customer support.

Beth and SamCouldn’t have been a better or easier transaction! Again, many thanks.

Betty D.When I first saw the painting, it reminded me of a time gone by, when life was so much more simple, where everyone was less in a rush, a time when everyone knew everyone, a time where people actually cared for their fellow man.

Bill B.It is a joy to have in our collection, and we will take good care of it, for the rest of our lives.

Bob L.We were so happy with Joan and Jerry’s customer service and expertise. I would recommend Bedford Fine Art Gallery to anyone that is looking for the special piece of art. You will be happy you reached out to them.

Bob and Christine M.Discovering Bedford Fine Art Gallery and working with Jerry and Joan to purchase our first picture from them has been a smooth and joyful experience — and we haven’t even met in person yet.

Bob and Theresa L.I drove 12 hours to meet the nicest couple and outstanding artwork that was perfectly and honestly represented. More than pleased with expertise, professionalism, and kindness genuinely exhibited by Jerry and Joan.

Brent & Sarah S.Thanks for making my purchase so easy.

Brian C.It was truly a pleasure dealing with you and the Bedford Fine Art Gallery.

Brian C.Greetings! Thank you for your periodic emails. They are always welcomed.

CNLove your posts…thanks!

CarrollA truly incredible website. Really! I was "detained" there for almost two hours and have returned periodically. Pictures are worth thousands of words, literally. Any reader who heeds our advice and visits the site will be happy to confirm our praise. We encourage all to visit and get to know Joan and Jerry. Most knowledgeable, friendly, accommodating, and a pleasure to deal with.

Carroll and Carolyn K.Joan and Jerry Hawk’s Bedford Fine Art Gallery, located in the historic Bedford Mansion, near the Bedford Courthouse, offers an extensive collection of original 19th century paintings in their beautifully restored gallery...which continually attracts this appreciative collector and former museum trustee.

Charles F.I would highly recommend this Gallery for art.

Christopher C.In this age of internet shopping, few can pull off personalized and professional customer service, but Bedford Fine Art Gallery has perfected it!

Christopher K.Furthermore after discussing its acquisition with Joan not only did I find the entire process most pleasant but Joan agreed to deliver the painting the very next day which was in fact my birthday. I find this sort of old-fashioned business courtesy so rare these days. What a pleasure to do business with people like this! I wholeheartedly recommend art purchases from this company! They are simply the best!

D. H.Jerry - The painting just came alive. Please know how grateful I am.

D.G.S.Jerry, - Thank you and Joan for our visit Friday. You two make me smile.

D.S.Magnificent. Your love for your art collection is displayed in your gallery.

Dave N.I was very pleased with the way the communication between Gerald Hawk and myself was handled. Very prompt and efficient. I would recommend the Bedford Fine Art Gallery to anyone interested in their beautiful artwork.

Debra B.I am enjoying my artists work and their position in my Mechanicsburg home, as well as Williamsburg.

Doris B.Jerry & Joan offered the work fully restored and framed so it was ready to hang. They were easy to deal with which went a long way since I was buying from outside the US.

Ed H.A visit to the Bedford Fine Arts Gallery is a rare opportunity to see American nineteenth landscape, portrait, and still life paintings in a house-turned-gallery of the same era, in a region close to where some of the artists, such as The Scalp Level School, painted.

Ellen C.We have counted on the Hawks over the years to regularly discover incredible items whose quality and condition have ameliorated the artistic environment of our homes.

Frank B.Thanks again for the opportunity to own the work of an artist who is very important to us. We are extremely happy with this experience. Take care.

Franklin J.My introduction to Gerald Hawk came through an initial phone call. Not only was he knowledgeable of fine art and well connected with the collecting community, he was passionate for his love of art. He treated me with the greatest respect, honesty, and kindness. That was the start of a business relationship that has probably been the most enjoyable I have had the pleasure to experience in my life.

Fred C.Just to let you know the painting arrived in perfect condition and we are thrilled.

G. & T.Beautifully done - one can tell it is a work of love! The collection was impressive and the viewing of it , a pleasure. Thank you!

Gabrielle G.Proprietors Joan and Jerry Hawk have established a first class art gallery offering the very best in fine art, professionally arranged displays, state-of-the-art technology, and superior customer service.

Gary G.Thanks for the quick reply etc. Not what usually comes from those Big Auction House Players .. and NYC galleries. So it’s refreshing to experience the response.

Geoffrey H.I recommend BFAG to both the serious art collector and to the one who desires to cultivate a love for fine art. The Hawks are knowledgeable and accommodating, and their love for fine art goes far beyond making a sale.

Gus S.Absolutely stunning art!

Irene and Peter E.Very pleased. Don't hesitate to contact me when you get something in that you think fits my collection.

J.M.The more I look at Rose Point the more I like it.

James M.The new paintings are hung and look great, thanks for delivering.

Janet S.I am so happy with my completed “gallery wall” and wanted to thank you for all your help in putting it together.

Janet and George S.Jerry and Joan are simply amazing. Their knowledge and passion are second to none. Not only is the collection at Bedford Fine Art Gallery of museum quality, but their passion really inspires you, comforts you, and welcomes you in as a member of what seems like an exclusive club. We are blessed to know them.

Jason and Alyson L.The Bedford Fine Art Gallery was recommended to us by our neighbors. They were very impressed both by the wonderful artwork presented and the very amiable owners. So, one rainy day, we stopped in to see for ourselves. We are so glad we did! It was immediately evident that, for Jerry and Joan, the gallery was not a business but a passion.

Jeff and Cathy D.It’s not every day you meet people so kind, professional and passionate about what they do. Every detail was taken care of from the excellent online listing to perfectly handled packing and shipping once we completed the purchase.

Jeff and Lisa G.From the front door, you can tell you are going to have a very interesting, pleasant and peaceful experience. The art is wonderful. The owners have so much knowledge and the patience to share it.

Jeff and Sara K.My testimonial for my purchase of the C. H. Shearer painting is a five star one!

Jeffrey F.Our impulsive stop while strolling through town turned into a several-hour visit and, ultimately, resulted in the purchase of a unique painting that we could not resist. The Bedford Fine Art Gallery is a destination must that we highly recommend for anyone who appreciates classic American art and superior service.

Jennifer T.Thank you for your help finding 2 new beautiful paintings for our homes!

Jeremy & AdrienneWe really appreciate the time you took to research the history of the roses.

Jim C.Jerry and Joan are terrific to work with. They have a wonderful selection in their gallery, and they take time to learn your interests to aide in the selection of a great piece of art.

Jim K.It was a pleasure working with Jerry and Joan at Bedford Fine Art Gallery.

Jocelyn D.Awesome place. Thank you for your hospitality.

Joe and Zoey K.Jerry and Joan Hawk have an extensive knowledge of the artists, backgrounds, and artwork in their gallery that they love to share with guests . The time invested in the Bedford Fine Arts Gallery will be one of your most pleasant memories of the year.

John B.A gem in the middle of Pennsylvania.

John and Kathy D.Beautiful and wonderfully displayed paintings.

John and Paula L.Hi Jerry, the painting arrived today and I think it is a beautiful and I’m very appreciative and thankful to have it.

JonSince the first time I visited the Bedford Fine Art Gallery it has been a great experience. The owners are warm, humble, and true professionals with amazing expertise to guide new collectors in finding the right piece that speaks to them. The knowledge and passion they share is so refreshing and made the entire process, from browsing to the final decision, so exciting and a true pleasure

Josh B.Extremely knowledgeable staff and wide selection of high end paintings by listed artists.

Joshua J.It was such a pleasure to purchase artwork from Jerry. He is an honest man, who goes the extra mile (literally – he actually delivered a painting to me, over 6 hour drive one way!) to make sure the painting arrived safely.

Julie A.Jerry was of great help by purchasing a painting that had been in my family for over sixty years.

Kenneth L.Packed with fine art like visiting an art museum

KevinHello Jerry, I love it. Just what I had been wanting.

Kevin V.Very informative, welcoming, absolutely gorgeous art. Thank you so much for the experience!

Kit T.Hi Jerry and thanks for your quick response!!!!!

KkThank you very, very much for your response and expertise.

LVMany thanks to you for your care and context in telling me more about the artist and the market!

Laura W.We were especially appreciative of your patience with us and your knowledge of the art.

Lee S.Dear Jerry, Thank you for so generously taking your time to research my painting.

Linda R.I just wanted to check in to see how you are to tell you that I was reminded yesterday of what an awesome business you guys have going. I went to one of the other galleries that has some of my artwork, and the person that I was dealing with no longer works there. Everything was mass chaos, and they can’t find one of my paintings! Jeff and I already knew that we found a gem when we found your gallery but then we got to spend time with you in December and it was doubly confirmed! Thank you again for letting us be a part of your beautiful Gallery.

Lisa G.Jerry: Got the paintings—they look fabulous.

M.M.If I could give more than 5 starts to Bedford Fine Art Gallery, I would. Dealing with Jerry Hawk was timely, efficient and productive. His terms made it possible for me to buy it, and he collaborated with a local shipping outfit to pack and send the painting as well. (It was beautifully and securely packed.) I recommend Bedford Fine Art Gallery without reservation!

M.P.Jerry and Joan were honest and straightforward with me. Also, they made the sale easy and fair.

Margaret H.The entire transaction was very smooth and I had excellent communication the entire time.

Margaret R.On a recent trip to Bedford we visited the Fine Art Gallery and were impressed by the quality of the paintings displayed and by the discussions we had with Jerry. We purchased a painting and we expect to revisit the Gallery on our next trip to Bedford.

Marguerite and BobI am thrilled with my purchase and cannot thank the Hawk’s enough for their exceptional customer service, and knowledge of the artist's paintings they carry in their gallery.

Marian B.The owners, Joan and Jerry Hawk, were very knowledgeable about each work of art in the Gallery and the art market in general. We found them to be very honest and sincere and never pushy about making a sale despite our interest in several pieces. A few weeks later we decided to purchase an oil painting from them. The overall transaction and delivery exceeded our expectations and we love the painting. If you are interested in purchasing a fine work of art from a dealer you can trust, I would highly recommend Joan and Jerry of the Bedford Fine Art Gallery.

Mark B.What a great experience it was to make my first fine art purchase with you. Thank you!

Mark S.We have been very happy with the entire purchase process, from choosing a piece of art to the care Jerry and Joan gave the piece in order for it to look perfect in our home.

Mary and Monty B.Jerry and Joan have a beautiful collection to choose from and provided exceptional customer service.

Melissa and John P.Jerry and Joan have a beautiful collection to choose from and provided exceptional customer service.

Melissa and John P.Thank you for all your assistance with my recent purchase. Both you and your wife were very kind and knowledgeable.

Michael M.When I'm searching for an artist, or a tone and style that I love, I turn to Bedford Fine Art Gallery.

Michael M.I keep coming back to your gallery because I love your paintings.

Michael M.Jerry and Joan Hawk have created a haven for art lovers!

Michal J.We consigned 3 oil paintings with Jerry and Joan Hawk at Bedford Fine Art Gallery.

Mike F.Jerry and Joan made it a smooth and wonderful experience by putting us at ease with their knowledge and gracious manner.

Mike and Karen S.It was such a pleasure to buy our first piece of fine art from you both.

Mike and Kelly C.Thank you for your business with the lovely paintings.

Moira O.We recently consigned several pieces of art to The Bedford Fine Art Gallery. It is hard to part with treasures, but Jerry and Joan were most accommodating in meeting us halfway in West Virginia. We appreciate their professionalism, received prompt payment for the sale of the first art piece and look forward to continued successful transactions.

Pam and Mike F.Jerry and Joan were a constant pleasure to work with. I had been considering purchasing a presidential portrait of theirs for some time, but they never tired of my questions or repeated requests to see the painting. I hope to acquire more 20th and 19th oil paintings in the future.

Patrick N.We are now excited owners of several beautiful paintings and look forward to seeing what new pieces are added to the gallery. Working with Jerry and Joan was a great experience.

Patty and Jim K.You are very honest and a man of your word. Thank you very much Jerry!

R.K.What a pleasant and surprisingly exciting experience, purchasing my painting from the Bedford Fine Art Gallery became.

R.T.From the first call through receipt of the expertly packaged artwork, the Bedford Fine Art Gallery excels!

Randy B.If you are able to visit the gallery I would suggest giving a few hours to enjoy the artwork. One more tip.... if your satisfied how the paintings look online, they are much better in person. I know I'll be back in Bedford soon to purchase another!

Randy Scott F.I would recommend this hidden gem!

Rhetta G.Jerry, thank you for overlooking my stubbornness and indecisiveness.

Rich C.They provided a simple and seamless transaction.

Richard and Cassie F.Ken came and delivered the art. Everything is beautiful.

Rick M.I would like to give a personal recommendation from my first-hand experience with the Bedford Fine Art Gallery during February and March of 2024.

Rob K.Jerry Hawk's passion and knowledge really shine in Bedford Fine Art Gallery's excellent collection of 19th century art. I heartily recommend Jerry and his gallery.

Rob S.We love the new paintings and are so glad to know you and your amazing gallery.

Robert L.The painting is exactly what I have been looking for.

Robert M.Truly, you are the "The Most Honest Art Gallery in the United States.

Robert M.It was a delight to have several hours with some very interesting and helpful people.

Roger and Joy G.Joan made us extremely welcome on that first visit and we were very taken with the work of two artists. We returned the next day and enjoyed a relaxed opportunity to study the pictures again before we committed to purchase. Both Joan and Jerry were very knowledgeable and helpful but also allowed us some privacy to discuss the pictures ourselves. Once we committed to purchase they went "the extra mile" to help overcome obvious hurdles of packing for international shipping and the customs arrangements.

Russell & Liz C.Joan and Jerry are extraordinary to work with for the purchase of our painting. They are extremely knowledgeable about the painting and have been helpful finding historical information about the Artist himself. Our beautiful painting hangs proudly where all can see and enjoy it.

Ryan M.If you are considering a wall art purchase to decorate your home, we would highly recommend contacting The Fine Art Gallery. We look forward to seeing what new pieces will be added in the newly expanded lower level of the gallery.

Ryan and TriciaThey were both very knowledgeable and truly care about each and every piece that they own. Ultimately, I was able to take home my very first John Joseph Enneking piece, Woodland Whitewater, and I could not be happier with both the piece and my entire experience at Bedford Fine Art gallery.

Sam H.This wonderful gallery is often noted to be on par with a 19th century art museum or salon and is not to be missed, including meeting its’ purveyors of art, Joan and Jerry Hawk. Their discerning eye, thorough research, and care in selecting and presenting the best representative art of the period is most impressive.

Sarah H.Upon meeting both Jerry and Joan I knew I made the right decision. They are very passionate about art work and quite knowledgeable on the life and history of the artist. It was a pleasure doing business with them and I would highly recommend the Bedford Fine Art Gallery if you are looking for fairness, honesty and a genuine comfort level in either selling or purchasing fine art.

Scott & BarbetteVisiting with no intention of buying, we were treated to in depth information on each artist and piece that caught our attention. We untimately purchased two pieces that touched us. Art speaks to everyone differently and it is nice to have gallery owners who appreciate that.

Sheila and FrankWe recently purchased a beautiful original oil painting from Bedford Fine Art Gallery. We live in Virginia, and because of Covid 19 and our age, we hesitated on traveling to PA to view this painting. Jerry and Joan were very accommodating. We highly recommend Bedford Fine Art Gallery, if you're in the market for some quality art work.

Sonny and Carolyn B.I bought three gorgeous paintings from this gallery and the owners are simply the best.

Stefanie L.What an incredible experience as I was on the search for a still life by BS Hays. Bedford Fine Art Gallery offers a beautiful, historical environment with a personalized service, guiding you through lovely art offerings.

Susan M.I am so happy to have worked with the Bedford Art Gallery; the people were pleasant and knowledgeable. Their collection is beautiful.

Suzanne F.I also wanted to thank you for your detailed response.

Suzanne S.We are enjoying the painting. Happy holidays to you.

TeddyThe breadth and depth of Jerry's knowledge of art is very impressive. What I especially appreciated was his down to earth manner and his willingness to know his customers.

Theodora BYou are wonderful Jerry! Thank you so much. I'm glad I connected with you. You certainly know your industry! I appreciate all of your help.

Tim B.Thank you- you are very kind.

Tim S.We found Bedford Fine Art Gallery about a year ago. Most impressive was the level of customer service they bring to the table. They went out of their way to be as helpful and accommodating as possible. We bought a wonderful painting we love.

Tim and Mary H.In sum, Bedford Fine Art Gallery is an exceptional art gallery which fosters meaningful relationships based on mutual respect, trust, and an appreciation for the field of art history. I highly recommend Bedford Fine Art Gallery and I look forward to forging a lasting relationship with Jerry and Joan for years to come.

Tyler M.Personalized, smart, customer service designed to assist you in choosing the finest 19th century paintings anywhere—whether you know your style & you’re adding to it, buying investment art, or like me—walking in and being starstruck by a piece that calls to me with no rhyme or reason but must come home with me.

Tyna L.Gerry was amazing to work with. Called him totally out of the blue, to sell a painting from my mom’s estate. Promptness is an understatement.

Uri S.Buying a favourite picture and talking with owners was a wonderful experience. Looking forward to seeing what they post for sale in the future.

V.B.Thank you so so much.

Valerie K.Combining knowledge and passion with their friendly home spun appreciation for their clients, the Hawks are the most delightful respite from the usual gallery sales approach.

Vivian and Bennett L.I really enjoyed the art, but the house, decore and overall experience was also very enjoyable

William K.Just arrived. Looks great. Thank you.

William M.We will undoubtedly visit again to see the art in this remarkable gallery. We brought home a watercolor and have the confidence we were dealt with openly and fairly.

William and Susan L.

230 South Juliana St.

Bedford PA 15522

Phone: 724-459-0612

All content and photos are copyrighted property of Bedford Fine Art Gallery, 19th century art dealer, Bedford PA and can not be reproduced or copied without consent.